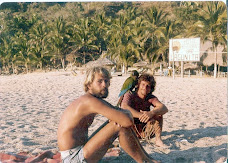

I spent five months in Yelapa in 1968, having come straight from two months in the Haight-Ashbury, where I put the finishing touches on my initial two years of psychedelic experience. I joined two friends who were already settled in a Palapa. I came to the Haight from Chicago, where I had dropped out of a PHD program in philosophy and where I had been teaching at a community college. This was the begining of my drop-out odyssey.

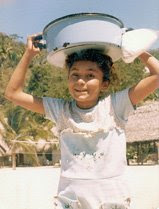

Yelapa in 1968 was a small rural Mexican village with only dirt paths and no electricity, which happened to be located in one of the most beautiful, easy to live in places on earth. An inlet in the large Bay of Banderas with a beautiful beach and minimal commercial development. As best I can recall, there were a few palapas for tourist rental at one end of the beach and two small restaurants serving basic Mexican food. There was hardly any boat traffic. Two small boats would bring day tourists from Vallarta, who would walk into the pueblo or take a tour to the waterfall uphill from the pueblo, guided by a local child. There were occasional small private pleasure boats, but the inlet was free of any ongoing boat presence. The water was clear and ideal for swimming. The formation of the inlet cut the currents so that it was like a salt water lake. I would do yoga on the beach and go for a long swim every day with no concern about an undertow.

Going up river from the beach I recall only some local homes and small plantations. I remember walking up river watching iguanas sunning on the rocks. There was only one path which ran uphill from the beach into the pueblo where simple dwellings were clustered along the coast and a short distance uphill for about half a mile. The center of the pueblo consisted of one store, a canteena and a small dock. There were a few local homes where people did some cooking or baking, made tortillas for sale. There were some basic palapas for rent to tourists scattered through the pueblo.

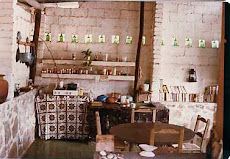

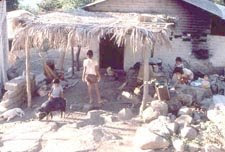

Walking on a path in Yelapa you were likely to encounter one of the village’s large sows trundling towards you, who would move off the path if you said “hutch” with authority. The paths were liberally strewn with animal droppings which the pigs consumed. You were also likely to pass chickens, horses, mules and donkeys. The children seemed especially fond of the donkeys. Whenever you passed someone, it was customary to greet them-“buenos dias señor”, “buenos tardes señora”. The pace of life was essentially aligned with the natural environment, not much sense of external pressure. There was no electricity and you seldom heard engine noise. People lived with kerosene lanterns and cooked on simple propane stoves or over open fires. Most nights it was quiet except for nature sounds. If there wasn’t much moon light, it was dark. I recall feeling enveloped in the pulsing rhythms of the insect life, which were more intense back then.

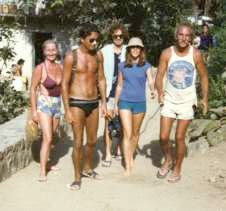

By 1968 the natural beauty, simple life style and affordability of Yelapa had begun to draw a small but steady stream of people from the psychedelic subculture who would stay for varying lengths of time. I came with three hundred dollars and stayed five months. I rented a basic but beautiful palapa, with a flush toilet and running cold water for twelve dollars a month. I ate simply, a lot of fresh fish from a local fisherman with whom I developed a friendship, Santos Hoya. Santos had a dugout canoe, cut out of a substantial tree trunk. He let me and my friend Ken, who was an avid fisherman, take the canoe out in the bay. Ken and Santos would fish together, Ken with his modern gear and Santos with heavy line wrapped around bleach bottles, the hooks baited with life forms Santos pried off the rocks with a crow bar. When he got a bite, he hauled in good sized fish hand over hand, no rod, no reel, no gloves.

At that point in time Yelapa was an extraordinary intersection of modern and pre industrial life. One image that remains in my mind is the women of the pueblo listening to transistor radios while washing laundry by beating it on the rocks in the creek. They did my laundry. It was the cleanest, freshest smelling laundry I ever had. For people like myself going through deep transformations of consciousness, it was a special gift to be able to experience this basic way of life in such a beautiful environment.

The fact that I could live there so cheaply was, of course, a function of an unjust inequality between the U.S. and Mexico, a dominant - subservient exploitive relationship. At the time that $300 was my total assets, but that was by choice. Back then I was more focused on my own personal evolution than on the underlying social injustice. I think to some extent I also rationalized that despite the poverty of most Yelapans, they were in many ways living more wholesome tranquil lives than people in developed economies. Looking back I didn’t know enough about their lives to make that judgment. I was mostly absorbed in my own trip and the counterculture I was a part of.

I don’t think most Yelapans related internally to the changes in consciousness we hippies were going through, but I believe a few did, my friend Santos being one. We communicated in Spanish, mine being very limited, so that much of our communication was intuitive, non-verbal. One day he walked into my palapa after I had dropped a tab of LSD. He took one look at me and said “you look different today”. I said “how so”. He said “there is more energy around your body”. He said this matter of factly like it was an everyday type of observation for him. I explained why there was this energetic difference and he accepted that explanation and said that drugs were OK for the Gringos but they made the Mexicans crazy. I’ve never met anyone else in my travels in the counter culture, the Buddhist meditation community, with that level of sensitivity, completely natural, not cultivated by any practice or enhanced by any substance. He had natural gifts that drew him to people like me. Yet he was also very much a man of his culture and like most Mexican men he was attracted to the Gringitas and the sense of sexual freedom in the counter culture. There was a particular young woman he expressed interest in and I asked him how he would feel if his wife, who had borne him 9 children, stepped outside their marriage. He looked at me directly with his big brown eyes and said “she would no longer be allowed in my house”. He understood completely the sense of double standard I was raising and he conveyed to me that was the way it was for his culture. We could have that kind of exchange heart to heart, without judgment. I don’t say that as in any way a justification of the double standard, just as an appreciation of the kind of communication we had and the complexity of his personality.

At that time there was not much interaction I was aware of between the hippies passing through Yelapa and the deep indigenous spirituality of the Huichols. I don’t remember any of their artwork in Yelapa back then. Somewhat later, Gringos who settled in Yelapa, like Isabel, developed a strong connection with them. As I was leaving Mexico after my five-months in Yelapa , I encountered a Huichol man as I was coming out of the Institute des Indios in Tepic, where I had purchased some Huichol art work. We had a brief conversation about the objects I had purchased. After we parted I felt deeply moved, on the verge of tears, just from that brief interaction. I was as sensitive and open right then as I’ve ever been. There was no way I could maintain that state and function in the world I was returning to.

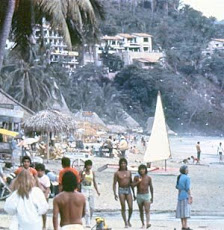

I returned for brief stays in Yelapa, once in the seventies and once in the eighties. After that second visit I felt that Yelapa had changed in ways that I could no longer relate to, still being so attached to that initial experience. Recently I ran into Cate Sims, an old friend from the Sonoma Valley, who told me she lived in Yelapa part of the year. I thought maybe a further transformation had occurred that might have turned Yelapa into a place I could enjoy again, now that so much time had passed and I could let go of any expectation that it would feel like the old days. That turned out to be the case. The proprietors of Casa Isabel, where I stayed, have created a beautiful environment that preserves the connection with the land, with a few amenities to be sure. The big beach where I swam every day for five months has succumbed to commercial development. I spent no time there on this visit, but I swam off Casa Isabel beach and in Pesota, and hiked up river. Fernando, who took a small group of us to the Mariettas for snorkeling, told us that there is pressure from some in the jurisdiction that governs development decisions, especially from those who live further inland, to really open Yelapa to Vallarta type development, but that so far the residents of Yelapa have successfully resisted. That would be the loss of what remains of a very special place, if Yelapa went the way of Vallarta. That’s for the locals to decide. From my perspective as an environmental attorney, the most likely scenario is that by 2050, if not sooner, as a result of climate change and sea level rise, the low lying areas of Yelapa, including the big beach, parts of Casa Isabel and other houses near the water, will be under water. I doubt that the developers are planning for that. In the meantime, I plan to spend more time in the current Yelapa.